A Three-Dimensional Model for Identifying Untapped Opportunity

By Kathy Booth

Even if they have never taken an economics class, most people are familiar with the concept of supply and demand. The concept sounds simple on its surface. If there is an increased societal demand for a particular item, we either ramp up production to meet that demand or hike up the prices. However, it’s not that simple, particularly when it comes to the present job market, where we don’t have enough people with the skills to fill available jobs.

Currently, we use a two-dimensional supply-and-demand model to identify sought-after occupations: The number of job openings is compared to the number of people who have graduated with a degree or certificate in a related field. This works well for disciplines like nursing or welding but not as well for disciplines like sociology or philosophy.

Nevertheless, this two-dimensional labor market approach shapes the priorities of governments, institutions, and individuals. For example, it is used by the Bureau of Labor Statistics to identify which fields of study have a bright outlook for hiring. K–12 institutions and community colleges prioritize which career-related courses to offer based on crosswalks of educational and occupational codes. This is also true for programs developed by workforce boards that support unemployed people to find work. Planning tools that help high school students determine which major or career to pursue are based on this same information. And many states may opt to use two-dimensional models to determine which programs meet requirements for Workforce Pell.

There are five reasons why a two-dimensional labor market approach skews our understanding of the skills gap and how to prepare people for in-demand jobs.

- Some educational programs are stepping stones to further education. Educational programs may not align with a particular job in the labor market because they prepare students for required further education. For example, a general studies associate degree might be a good first step toward becoming an elementary school teacher, which is a high-demand job in most communities.

- People don’t always choose a related job. Large-scale surveys conducted by the U.S. Census have shown that students may not pursue the occupations that are crosswalked to specific majors. For example, many psychology majors become managers, while a significant number of business majors work in information technology.

- People learn skills through programs that are not included in calculations. Most states do not capture information on people who prepare for work through noncredit programs offered by trade schools, adult schools, and community colleges, or through nonacademic bootcamps and employer-sponsored programs, even though the flexible nature of those offerings are better suited for adult and low-income learners.

- People change careers over time. Demographic shifts are tilting the job market toward older workers. As fewer young people enter the workforce, analyses that emphasize the majors of 22-year-old college graduates will miss the 52-year-olds who may be competitive for the same positions based on skills learned on the job.

- Employers look at qualifications gained outside of school. As industry shifts to a skills-first hiring approach, applicants’ college majors will no longer be the primary determinant for job eligibility.

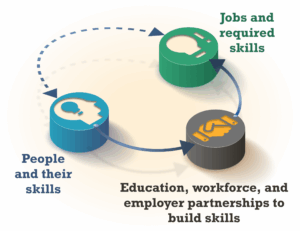

Two-dimensional supply-and-demand models are too simplistic to develop solutions for the skills gaps that define the current job market. If we want to provide people with comprehensive information about career opportunities, support them to describe their relevant skills, and change hiring practices, we need to use a three-dimensional approach to labor market information. Rather than use college majors as the way to evaluate job readiness, analyses should be based on skills. This would entail identifying (a) people who are seeking jobs and their existing skills; (b) the skills required for available jobs; and (c) the partnerships between employers, educators, and workforce training providers that would help people fulfill those requirements.

For example, to address the need for more elementary school teachers, we could focus on the paraprofessionals who already work in elementary schools instead of just looking at the number of people currently enrolled in teacher credentialing programs. Teachers’ aides, food servers, and after-school program staff have some of the skills required of teachers. With the support of postsecondary education, teacher credentialing bodies, and school districts, these workers could receive academic credit for their skills, attend programs that fit around their work schedules, earn credentials that recognize skills attained on the job, and advance to new positions in their schools.

WestEd’s Center for Economic Mobility is implementing a three-dimensional labor market approach in a number of projects. For example, we are supporting an initiative that is jointly offered by the California Community Colleges and the United Domestic Workers (UDW). Domestic workers provide in-home support to children, the elderly, and people who are disabled. These jobs require long hours and physical strength but do not pay a living wage, do not have consistent schedules, and often lack health care. The UDW members who are participating in the initiative are predominantly women of color over the age of 40, many of whom are not fluent in English.

To help UDW members identify academic programs that will help them make progress toward their goals, WestEd examined jobs that require similar skills as domestic work, do not require a bachelor’s degree, and continued to be in high demand through both the Great Recession and the COVID-19 pandemic. This information was shared with the colleges participating in the initiative at daylong design sessions where they learned about their regional labor markets, the characteristics of UDW members who live near their colleges, and their interests. Educators identified related programs at their colleges and determined the types of supports that would foster success, like offering English as a Second Language courses that teach medical terminology to help UDW members advance in an allied health pathway. To date, nearly 600 union members have enrolled in college.

In order to build stronger pathways to opportunity, educators, workforce training providers, and employers need a better understanding of both preparation gaps and untapped expertise. By using a three-dimensional approach, we can move from maps that sketch an idealized path to the nonlinear reality of career progression.

Want to learn more? Watch this recent Learning Society webinar that features two projects in which the Center for Economic Mobility is using the three-dimensional approach.